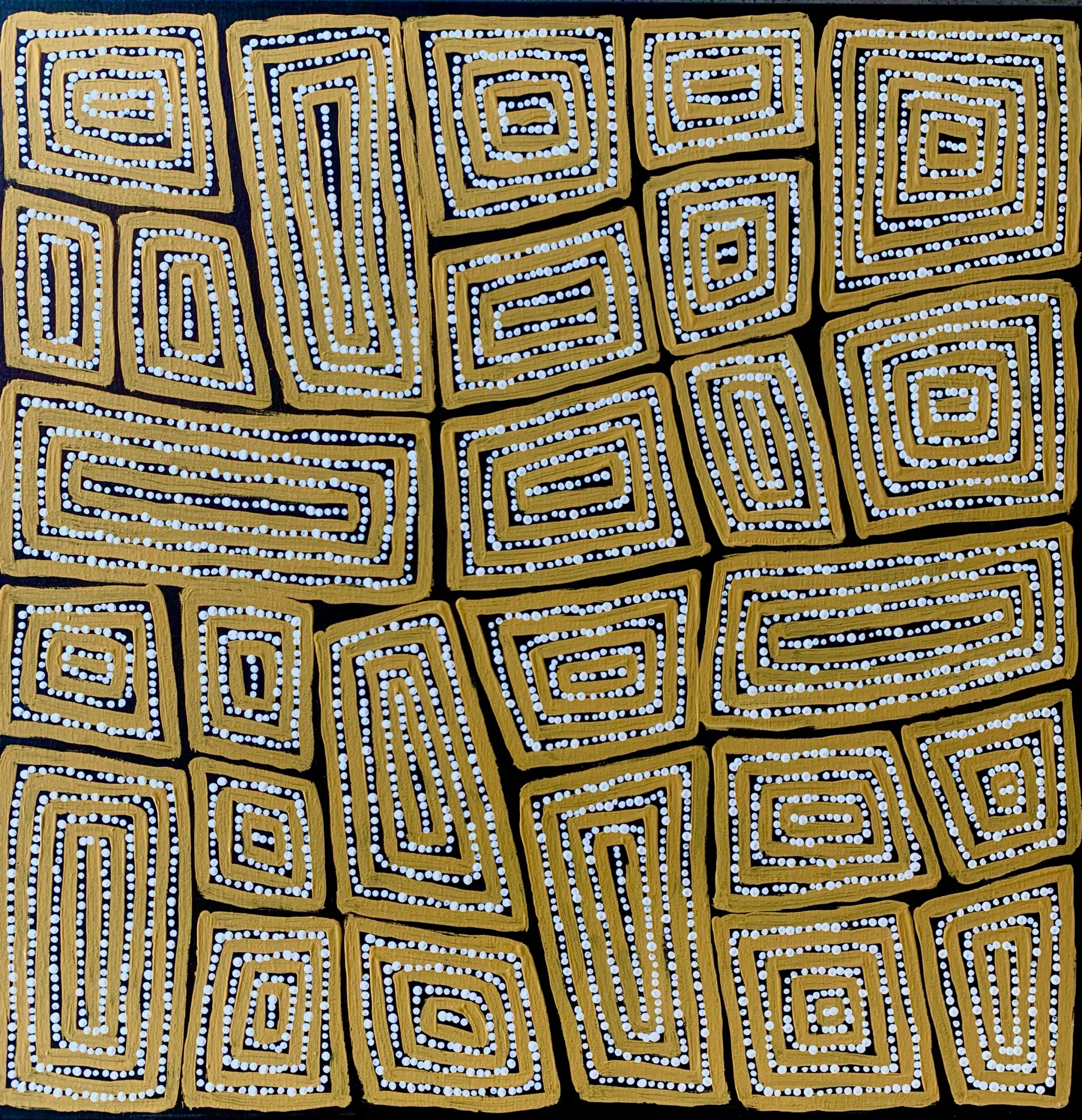

Example of a contemporary Aboriginal dot painting (“Tingari Cycle” by Thomas Tjapaltjarri). Dot patterns like these encode a Dreaming story through concentric motifs. The Tingari Cycle is a creation story from the Western Desert, often depicted with repeating square or roundels surrounded by dotted pathways.

Aboriginal dot paintings are instantly recognizable with their fields of colourful dots forming patterns and symbols. But how did this art form develop, and what do those dots really mean? In this article, we delve into the history of Indigenous Australian dot art, explore its cultural significance, and offer insights for art enthusiasts interested in collecting these mesmerising works.

The Origins of Dot Painting in Aboriginal Art

t may surprise many readers (especially those who’ve admired Aboriginal art for decades) that the famous “dot painting” style is a relatively modern development in Indigenous art. While Aboriginal peoples have been creating art for tens of thousands of years – from rock engravings to body painting and sand drawing – the specific practice of painting canvas or board with acrylic dots began in the early 1970s in the Central Desert region .

Reference: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/arts/are-dot-paintings-traditional-aboriginal-art

The story of dot painting’s origin centers on a remote community called Papunya in the Northern Territory. In 1971, a young school teacher named Geoffrey Bardon was working with Aboriginal children in Papunya. He encouraged the children and later the community’s men to paint a mural on the school wall based on their traditional Dreaming designs . This sparked great enthusiasm among the Elders, who until then had drawn sacred designs in the sand or on ceremonial objects but had not translated them to permanent media. Soon, senior Aboriginal men began painting their cultural designs onto boards and canvases using whatever materials were available (at first bits of wood, cardboard, even linoleum tiles) . They depicted Dreaming stories – sacred narratives of ancestors and country – using concentric circles, journey lines, animal tracks and other symbols.

However, these early paintings raised a challenge: some of the symbols were sacred and not meant to be seen by uninitiated eyes (including women, children, or outsiders). The artists ingeniously solved this by camouflaging certain sacred elements with dots . They painted fields of dotting over or around sensitive motifs, partially obscuring them. This not only protected sacred knowledge, it also created a visually distinctive texture – a dotted aesthetic that captured the imagination of the art world. Over time, what began as a method to veil meaning became an artistic signature of the Western Desert. Art historians often remark that this “layering of dotting” is the essence of Papunya painting: it allows multiple layers of meaning, where only the initiated can fully interpret the hidden story

By 1972, the artists of Papunya (now often referred to as the Papunya Tula Artists) formally established a cooperative to market their works . This collective was entirely Aboriginal-owned, ensuring artists controlled their output and income. It was a groundbreaking moment – sometimes hailed as “the birthplace of contemporary Aboriginal art” . The paintings coming out of Papunya in the 1970s gained national attention for their striking contemporary beauty and deep cultural authenticity. They effectively launched what is now known as the Western Desert art movement, which over the following decades spread to other communities across a vast area of Central Australia (including places like Yuendumu, Utopia, the APY Lands, etc.). Dot painting became a unifying visual language of this movement, even as each community introduced their own colours and variations.

Reference:https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/collection/highlights/papunya-collection

By the 1980s, women of the desert communities also began to paint on canvas (initially, only men painted, partly due to the sacred nature of certain Dreamings). Renowned women artists like Emily Kame Kngwarreye from Utopia emerged and took dot painting to new heights – Emily’s huge fields of dotted color, for example, conveyed the wildflower bursts in her Country and garnered international acclaim. What started in Papunya had, within a couple of decades, spread and evolved. Today, dot paintings are globally recognized as an icon of Australian Aboriginal art. They hang in major museums and galleries around the world, and are avidly collected. Papunya Tula Artists, the pioneer cooperative, is still active and celebrated as one of the most successful Indigenous art cooperatives – truly a testament to the legacy of those early dot painters .

(For those interested, the National Museum of Australia holds one of the largest collections of early 1970s Papunya dot paintings – an assemblage often cited as transformative in Australian art history, showing how those first dotted canvases “transformed understandings of Aboriginal art”

Cultural Meanings Encoded in the Dots

At first glance, an Aboriginal dot painting might appear as an abstract pattern – fields of dots creating shapes or merely decorative motifs. But for Indigenous people, these paintings are far from abstract. They are profoundly representational, just not in the Western figurative sense. Instead of depicting a landscape from a single viewpoint or a literal scene, Aboriginal dot paintings use symbolic icons and an aerial perspective to narrate a story, often one from the Dreamtime (the creation era, which to Aboriginal people is a ever-present spiritual realm).

Common elements in dot paintings include: concentric circles, which usually represent important places like waterholes or camp sites; parallel lines or meandering lines, which can indicate travel paths, water flows, or shields; and tracks or footprints, like those of kangaroo, emu, or human, which show the presence and movement of ancestral beings. These symbols are arranged across the canvas to map out events of a story or the features of a particular tract of land. The dotting itself may fill the background or outline shapes, and it can signify things like rain, sparks, stars, or just serve to obscure and “keep secret things hidden in the paintings” .

For example, in the Tingari Cycle painting by Thomas Tjapaltjarri (shown above), the series of nested rectangles with dotted borders represent locations and events from the Tingari Dreaming – a narrative about ancestral beings who traveled the desert creating features of the landscape and imparting sacred knowledge. Each rectangle shape could be a sacred site or camp, and the dotted lines are the paths connecting them (the journey of the Tingari ancestors). Only initiated Pintupi people fully know the story, but the painting communicates it on multiple levels – to other Indigenous viewers it’s a sacred map; to the uninitiated, it’s an intricate geometric design that still evokes a sense of journey and connection.

One beautiful aspect of dot paintings is this layered meaning. As an older collector or viewer, you can appreciate the painting aesthetically while also knowing that there are deeper meanings, some of which you might learn if they’re public and others which remain respectfully concealed. It adds a mystique and depth to the artwork. Indigenous artists often enjoy that their works operate on these two planes – open interpretation for a general audience, and specific cultural story for those “in the know.”

Colour is also symbolic. Early Papunya works were typically earthy – using desert reds, yellows, blacks and whites – mirroring the ochre colours used traditionally in sand and body art. Over time, as acrylic paints became more available, artists expanded their palette. Utopia artists, for instance, became known for lush brightly coloured dot art (thanks to women artists like Minnie Pwerle and her kin who depicted bush plum Dreamings in vivid tones). Meanwhile, some Western Desert artists like those from Yuendumu might use a restricted palette for ceremonial reasons (e.g., only red, white, yellow, black which have certain meanings). As a collector, it’s fascinating to observe how colour choices can differ by region or artist – sometimes influenced by landscape (the green of new vegetation after rain, the purple of desert sunset) or by personal style.

It’s important to mention that while dots are a hallmark, not all Aboriginal paintings from dot-painting regions use dots exclusively. Some artists use a mixture of dotted areas and solid color blocks or figurative elements. For instance, famous artist Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri did dotting but also included figurative silhouettes of ancestral figures or animals in his works. However, the dot motif remains dominant and is often what captivates viewers. It has even inspired artists in other media and cultures. But remember, for Aboriginal artists, dotting is not just an aesthetic choice – it’s tied to story and, originally, to the necessity of cultural protection.

Dot Paintings in the Art Market – A Collector’s Perspective

Over the last few decades, Aboriginal dot paintings have become highly collectible. Many older art collectors in Australia and abroad began acquiring these works in the 1980s and 1990s as their significance became evident. By the 2000s, major auction houses were selling important pieces for record prices. For example, works by the late Emily Kame Kngwarreye (who is often referred to as one of Australia’s greatest contemporary artists) have fetched very high prices internationally. In one Sotheby’s New York sale, Emily’s large dot painting “Summer Celebration” (1991) was estimated at $300,000–$500,000 – illustrating the strong demand and respect for top-tier dot art . Similarly, auction records show many Western Desert artists’ pieces achieving significant figures, indicating a mature market.

For a collector, what does this mean? Firstly, the value of dot paintings can vary widely. Emerging artists’ works might be priced in the hundreds or low thousands (affordable for those starting a collection), whereas works by “blue-chip” artists (the founding Papunya artists or later stars like Emily Kngwarreye, Clifford Possum, Judy Napangardi Watson, etc.) can be tens of thousands or more. As an older collector, you might recall some of these names from news of exhibitions or awards in the past. Building a collection can be approached in two ways: for passion or for investment (or a bit of both). If it’s purely for passion, you simply buy what you love and what story resonates with you. If investment is a factor, you might focus on artists with an established reputation or whose works are held in major galleries. However, one of the joys specific to Aboriginal art is that even relatively unknown artists can produce absolutely stunning works – because they draw on rich cultural heritage – so there’s much to discover beyond the famous names.

When collecting dot art, consider the following practical tips:

Engage with the Artist or Community: Some galleries arrange artist talks or have information about the community an artist comes from. Engaging with these can greatly enhance your appreciation. For instance, if you learn that an artist comes from the Pintupi group and returned to their homeland in the Western Desert as part of a community movement, it contextualizes their paintings of country – you realize those abstract patterns represent very real sandhills, rockholes, and soakages that the artist or their family know intimately. This connection between art and landscape is something quite special in Aboriginal art – it’s often been said that these paintings are maps of the soul as much as maps of the land.

Provenance and Authenticity (again!): This was covered in the previous article section but cannot be stressed enough. Ensure any dot painting you buy comes with authenticity documents and artist info. Given the high values involved in some cases, provenance is key. Established galleries like AMAGOA will provide certificates and are transparent about sourcing (e.g., they obtain works either directly from art centres or from the artists or reputable dealers, always following the Indigenous Art Code) . If you’re acquiring an expensive piece, you might even request additional proof like a photo of the artist with the artwork (some art centres provide this). The pedigree of a piece – including past exhibition history if any – can greatly affect its collectability.

Condition of the Artwork: Acrylic dot paintings are generally hardy, but check that the canvas is not sagging or paint flaking (older works from the 70s might have some condition issues due to experimental materials back then). If you buy from a good source, they usually ensure the artwork is in good condition or will inform you if there’s any minor flaw. When framing, use UV-protective glass or acrylic if the work is on paper, and avoid direct sunlight on paintings to prevent any fading over decades. It’s wise for significant pieces to be professionally framed for both display and preservation.

Display and Lighting: Dot paintings can have almost optical effects under different lighting. Many contain fascinating visual rhythms – as you step closer, you see the thousands of tiny dots and perhaps subtle color variations within them; stepping back, you see the grand design. Consider track lighting or ceiling lights to gently illuminate the textured surface; the interplay of light can enhance the dimensional feel of thickly applied dots. For large pieces, ensure you have a wall with enough space for the painting to “breathe” – they are statement pieces. Also, consider rotation: some collectors rotate the art between rooms or in and out of storage so they can appreciate different pieces at different times (or to give a room a fresh look every so often).

Learn the Language of Symbols: To truly enjoy your dot painting, over time you might learn more about its symbols. There are books and online resources that explain common Aboriginal art symbols (for example, a U-shape often means a person seated, wavy lines can mean water or rain, etc.). While each painting has its specific context, being able to recognize general symbols can enrich your viewing. You start noticing, “Ah, there are four U-shapes around a circle – that likely means four people sitting around a campfire or waterhole.” This turns viewing into an interactive experience, almost like deciphering a code (with the knowledge that part of the code will remain with the artist, which is fine).

Engage with the Artist or Community: Some galleries arrange artist talks or have information about the community an artist comes from. Engaging with these can greatly enhance your appreciation. For instance, if you learn that an artist comes from the Pintupi group and returned to their homeland in the Western Desert as part of a community movement, it contextualizes their paintings of country – you realize those abstract patterns represent very real sandhills, rockholes, and soakages that the artist or their family know intimately. This connection between art and landscape is something quite special in Aboriginal art – it’s often been said that these paintings are maps of the soul as much as maps of the land.

Appreciating the Beauty and Wisdom in Dots

What draws many older art aficionados to Aboriginal dot paintings is not just their beauty, but the sense of timeless wisdom they emanate. Each dot, carefully applied, can be seen as a metaphor for a piece of knowledge or a connection in a larger system. Together, the dots form a whole – much like individuals form a community, or moments form a lifetime. The philosophy embedded in Indigenous art – of interconnectedness, of humans and nature being part of one continuum – resonates deeply, especially as we age and seek meaning in the world around us.

When you hang a dot painting in your home, you’re not just decorating; you’re inviting a presence that is at once ancient and contemporary. Many collectors describe a feeling of calm or groundedness when living with these artworks. The repetitive dot patterns have a meditative quality. There’s also the dynamic that each viewer might see something different in an abstract dot design, making it a great conversation piece with guests. One might see blossoming flowers, another sees galaxies of stars – both perhaps equally valid, given Aboriginal cosmology often equates land with sky and microcosm with macrocosm.

For older readers who perhaps have traveled or seen much art over the years, Aboriginal dot paintings stand out as truly unique to Australia, yet universal in their appeal. They bridge a gap between ancient tradition and modern art abstraction. It’s noteworthy that art critics have often compared them to Western abstract art movements – the Papunya painters were sometimes likened to the American abstract expressionists or European modernists, though in truth the Aboriginal artists were guided by their own cultural frameworks, not by global art trends. Still, the fact that dot paintings can comfortably be appreciated alongside any modern art speaks to their versatility and depth.

If you’re considering collecting Aboriginal dot art, start with what speaks to you. Maybe it’s the color palette of a piece that delights you, or the intricate complexity of another that you can get lost in. Read the story of the painting if provided – knowing it depicts, say, the “Seven Sisters Dreaming” (a star myth) or a “Lightning Dreaming” might add a new layer of appreciation. Over time, you might find yourself with a collection that not only beautifies your living space but also becomes a repository of stories and knowledge that you’ve gathered – a very fulfilling endeavor.

(Internal link suggestion: You can view some exemplary dot paintings in our gallery’s collection, such as Thomas Tjapaltjarri’s “Tingari Cycle” or works by artists from Utopia, by visiting our online collection page. Each piece includes background on its story and artist, enriching the viewing experience.)

In conclusion

Aboriginal dot art is far more than just “dots on a canvas.” It represents a profound cultural innovation – a way for Indigenous Australians to share elements of their heritage with the world, in a form that protects what must be kept secret while inviting everyone into an appreciation of the beauty of their stories. For older art lovers, engaging with dot paintings can be both aesthetically pleasurable and intellectually stimulating, opening a window to one of the world’s oldest continuous cultures.

When collecting or simply admiring these works, remember the layers behind the dots: the history of Papunya where it all began in 1971 , the sacred stories cleverly encoded in paint, and the individual artists – many of them elders – whose hands and hearts bring these paintings to life. Each dot is a testament to cultural survival and artistic brilliance.

Whether you are looking to buy an Aboriginal dot painting for your home or just seeking to understand them better, approach it with respect and curiosity. Attend exhibitions if you can, browse trusted galleries, and feel free to ask questions. Most importantly, let the artwork speak to you. Stand before a dot painting and allow your eyes to drift over the maze of patterns – you might find it almost has a rhythm, as if the painting is a song silently humming. That is the power of this art form: it engages multiple senses and realms of thought.

Finally, if you decide to acquire a piece, do so knowing you are also becoming part of the story. You become the next chapter in that artwork’s journey – from the artist’s remote community to your wall, bridging worlds. It’s a truly special connection. Enjoy the journey of exploration that Aboriginal dot paintings offer, and the touch of the Dreaming they bring into everyday life.

(To learn more about the Western Desert dot painting movement, the National Museum’s article on the Papunya collection provides a great historical overview . For insight into how to interpret Aboriginal art symbols, resources like the Creative Spirits site (e.g., article “Are dot paintings traditional Aboriginal art?” by Jens Korff) explain the context of dot art’s emergence and meaning . Art aficionados may also enjoy visiting museum exhibitions or galleries dedicated to Indigenous art – for instance, the Art Gallery of New South Wales and National Gallery of Victoria frequently display Aboriginal desert paintings as part of their Indigenous collections, offering a chance to see these masterpieces in person.)